The textile industry in Eritrea is italian – EritreaLive interview with Pietro Zambaiti, D.G. of ZaEr, Zambaiti Eritrea

THE TEXTILE INDUSTRY IN ERITREA IS ITALIAN – ERITREALIVE INTERVIEW WITH PIETRO ZAMBAITI,D.G. of ZaEr, Zambaiti Eritrea

©Antonio Politano for EritreaLive, Asmara Za.Er, Zambaiti Eritrea, Textile Factory Asmara

Pietro Zambaiti, Chairman of the Board of Za.Er, Zambaiti Eritrea travels back and forth from Bergamo and Asmara, the capital of Eritrea, where he manages his family-run textile industry.

Cotton has always been the Zambaiti’s spirit. His grandfather started dealing with textile trade since he was young. In 1948 he founded the first core of the business, which later became the Zambaiti Group. In the Sixties, the cotton mill was born with Giancarlo, father of Pietro Zambaiti.

In 1992, when the Italian textile industry was going through a delicate transformation phase, the Zambaiti family bought the Honegger cotton mill.

A history which ended twenty years afterwards, in 2012, when the historic cotton mill of Albino stopped activities.

It was traumatic for a business, which was a symbol of confidence, with work being passed on from mothers to daughters for generations. It was a way for young women to secure ol pa’n’véta, “bread for life”, which is also the title of the documentary describing the sad crumbling of the textile industry of Bergamo.

My father started an industrial group which, in the years when the textile sector in Italy is an important reality, has more than 1,000 employees – he explains

Pietro Zambaiti, interviewed by EritreaLive in Bergamo

Asmara, Pietro Zambaiti with Eritrean professional road racing cyclist, national champion, Daniel Teklehaimanot

What happened next?

Let’s start from the date when we bought the Honegger Cotton Mill of Albino in 1992. That was a significant date.

In 1993 in Italy the euro had not been introduced, yet (editor’s note, 1st January 2002 the euro was introduced in Italy, three years before then the euro had become the official European currency) and with the lira Italian enterprises took advantage of interventions on exchange rates, with periodic devaluations. And if that wasn’t enough, Europe decided to sacrifice the textile industry, abdicating to Chinese competitiveness.

Crisis in Europe, development in China. In China there are many quality products. A condition, allowing them to be competitive in the mid-market, leaving the Italian and European textile in the niche market. And for us that meant death. It wasn’t possible. Furthermore, in 2008 the crisis hit us, nullifying any possible attempts to make it. In the Honegger history the macro economy, as well as the territory were involved. There were many failures, which made both our efforts and our workers efforts to resist vain.

Was that a turning point for you?

Yes. Originally, the Honegger cotton mill produced textiles only in Italy. To be more competitive and to offer better service to our customers we had the absolute necessity to internationalize and verticalize production.

In 1993 my father decided to go to Eritrea.

Immediately after Eritrea became independent?

Yes. In those years Eritrea planned to privatize some businesses. (Editor’s note, private businesses had all been nationalized by the Ethiopia of Menghistu Heilemariam). In Eritrea my father saw the difficult conditions, but also the Country’s perspectives. So he proposed the Government to re-start the textile industry. He asked to receive as a gift what was left of the old textile factory “Barattolo” paying a symbolic price of a dollar for it.

And what remained of that factory?

Nothing. Many resources were required, new technologies, staff training. Also because the long fight against Ethiopia (Editor’s note, 1961-1991) had interrupted life in Eritrea.

The Government refused initially, Then, after a few years, it accepted. At that point our family returned to Eritrea. We saw that the work to be done was huge, but we also saw the positive aspects. For example, the friendly attitude of the people.

So you decided to start?

Yes. We took the challenge, also because both my father and myself already had a good relation with Africa. In previous years we had been in Ghana to help a missionary. I co-ordinated the logistics side in Italy and the donations for this [Daniele] Comboni’s centre.

30 years ago I was already dealing with the integration of immigrants arriving in Italy. Together with some friends I had set up an association called ChiaroScuro.

So you left for Eritrea?

No. It was in 2004 and I remained in Italy to follow the production of textiles of the Honegger cotton mill.

But I dealt with the relations between Italy and Eritrea. I always thought that Italy could play an important role for Eritrea. It is true that an effort is needed from the Eritrean side, but Italy can be the player of the match.

So, from the very beginning I flanked delegations coming from Italy. I think it is important that a company like our own, employing hundreds of people, gives its own contribution to the development of the Country hosting it.

However, when the Italian textile story ended, in 2014, I left for Africa, destination Asmara.

StartAfrica began, an emblematic name chosen for the company.

Objective? Organization and sustainability, and then starting to grow.

Today data demonstrate that, even in a still evolving and not simple scenario, Za.Er is a model of responsible and sustainable business in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Za.Er inherited the industrial complex of the Barattolo cotton mill, founded by Roberto Barattolo in the Fifties. The factory then included a spinning mill (25 thousands spindles) and a weaving factory (424 looms). Can you stand that comparison today?

The Cotonificio Barattolo bears witness to the fact that you can do business in Eritrea. Barattolo, we stress, arrived in the Fifties, not in the Thirties.

That is, he arrived in the years when Italian colonialism had ended (1941) and there was Heilè Selassiè, who received Eritrea as a gift from the United Nations…

Also in those years Eritrea remained for Italy “the most developed region”, if you can say so. There was a middle class of entrepreneurs and a relation with the population with many shadows, colonialism, but also many lights.

This is demonstrated by the friendship between Eritreans and Italians. Eritreans recognize they have inherited buildings and learned jobs from the Italians.

Artisans and small enterprises, until the Thirties worked with Eritreans. Before then there were 70 thousands, even 100 thousands Italians, many of which did manual jobs. In the Seventies, instead, due to political events, Italians left Eritrea. 15 thousands remained. At that point the relation with Eritreans became even more crucial and close. They worked together.

Back to Barattolo. He arrived in Eritrea and made a fortune in the textile sector at a time when textile went well also in Italy. It was the world market that was growing. The end of the “Barattolo” coincided, instead, with the nationalization implemented by the Ethiopian military government.

Did Barattolo also own cotton fields?

Yes. And he was not the only one. The Italians, in the Thirties and Forties, had received concessions of fields to cultivate cotton.

Cotton needs water and warm weather to grow. In Eritrea there is no lack of warm weather. Rain is seasonal, instead. But if you build dams to hold water you can irrigate and make the fields fertile even when it doesn’t rain.

Nowadays the Government has built new dams, an essential condition for agricultural development.

But for cotton, apart from all that, you also need a comparative analysis with other countries, both for soil conditions and for climate conditions.

Also for its production you need a new way of working. This is why we have brought Italian and Romanian workers to Eritrea. Their job was to train Eritreans who would then take over. Also for the cultivation of cotton a transfer of skills would be needed.

Where did you grow cotton in Eritrea?

In the Alghidir estate, near Tessenei, close to the border with Sudan and in other concessions like Kerkebet.

In Eritrea, ideally, as the President Isaias Afwerki himself wished, you could have two sowing times, one during the rainy season, and another using water from the dams.

It is important to produce good quality cotton. For this you need the co-operation of specialists.

Sure, we would like to buy Eritrean cotton. Without it you cannot have any spinning.

If you do not grow it on the spot you waste too much energy and water to transform a raw material coming from from other African Countries. It is not convenient for anyone.

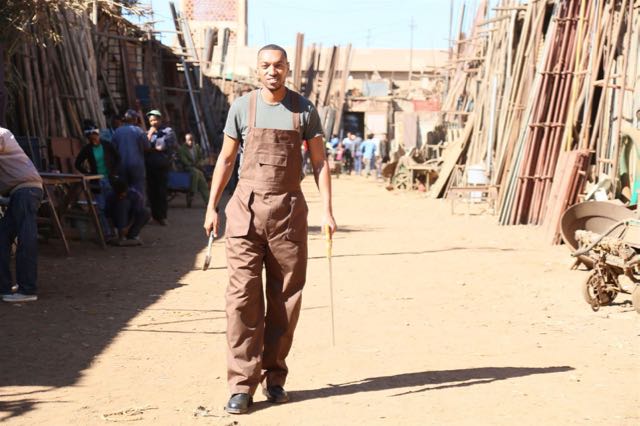

Medeber, caravanserai of Asmara, a worker wears a Za.Er uniform for work

Za.Er today produces shirts and work clothes, for both civil work (offices, hospitals, schools, hotels) and military work. Our goal for the next two years is to export work clothes in the COMESA area (Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa), the common market of Western and Southern Africa.

Starting from countries like Sudan, Uganda and Kenya. If relations, as we hope, should improve an important market would be Ethiopia. The success of Barattolo was obviously determined by the Ethiopian market.

In 1975 Barattolo employed 2,000 workers, above all women. How many are there now?

Today Za.Er employs 550 people, which in comparison with two-thousand may seem few, but it is a good number.

We can still grow. The positive thing is that workers are all Eritreans and 85 per cent of them are women. With two exceptions, the director general in charge of production growth, who is Indian and the production specialist in charge of improving quality.

Our goal is to double production in the next two or three years.

A goal involving the hiring of new staff?

Sure. We could increase up to a thousand people. Staff is important in production and Eritreans are very good, if they are well trained and co-ordinated.

We teach our staff a qualified job. Most of them arrive without experience.

What are the work conditions like?

The work conditions are good and salaries are higher than the Country’s average.

We stress that women, as I said before, not only represent 85% of the workforce, but also perform most of the managerial and staff positions.

Also for this reason we give an extra service to families, a day nursery for their children and bursaries for the Scuola Italiana. Today we have approximately 100 children – some are our own employees’ children and some are from other families – and we are planning to increase this space in 2018. So we could receive approximately other forty children.

©EritreaLive, Asmara, Za.Er Cotton Mill, Zambaiti Eritrea, the day nursery for employees’ children

As I mentioned, we follow the path of the children as they grow. They can take a test for admission to the Scuola Italiana. If they pass it and are accepted, we help them. If necessary they are also helped with their homework in the afternoon. The number of helped children is bound to rise, something we are proud of as it reflects our mentality.

We are happy to be able to offer bursaries to our employees’ children.

Are the women working for Za.Er heads of the household? Is their salary the most important one?

It often is so.

How do you envisage the future of Eritrea and of Za.Er?

We continue to think that Eritrea and Eritreans deserve more than what they have now. I think that Eritreans hoped for a better future when they were fighting for independence. Without forgetting the best part of their past and our past.

They had to come to terms with a series of situations, also external ones, which hindered the growth process.

Today, however, the geopolitical conditions could see Eritrea play a major role, even if the international scenario remains complex and difficult.

Surely, co-operation with Italy would support its development.

It is important to choose the right interlocutors and to build relations built on mutual trust.

We, as a company try to commit ourselves to make this happen.

Are you working for a better relation between Eritrea and Italy?

Yes. With a positively evolving international scenario, Italy could be a partner for Eritrea, a country with a strategic geographical position, something which we cannot ignore.

In the COMESA area there are approximately 600 million people.

Italy and Europe could have an important role in Eritrea, above all trying to improve relations with Ethiopia.

©EritreaLive, Asmara, Dolce Vita, brand Za.Er in the central Harnet Avenue

But what does Italy do?

Unfortunately, in Italy there is a total ignorance about these subjects. A lack of knowledge of history, our own history and the history of Eritrea.

A history that we’d rather forget than let it become a contribution for the wealth of the Country.

This is the reason why, in Italy itself, Eritrea is forgotten, hindered. If today we asked where is Eritrea, many Italians could not answer.

They confuse it with Ethiopia…

A careless repression?

History cannot be ignored. Eritreans know history and the relation between Eritrea and Italy. Without excusing colonialism in any way, it must be said, though, that in Eritrea Italians felt Eritrean and Eritreans felt Italians.

For this reason Eritreans have resented Italian betrayal. They appreciate Italian culture. Otherwise they would not line up to attend the Italian School in Asmara. They have a knowledge and an attachment to Italy, which is much stronger than required by the “ius soli”.

However, paradoxically, with the worst possible management of the migratory process, an Eritrean person in Italy feels discredited. Cannot feel recognized. So they will go elsewhere, to Germany or Sweden. Europe, as opposed to Italy, chooses to receive honest and skilled Eritreans. We do no help them, instead.

Marilena Dolce

@EritreaLive

Lascia un commento